The Slovaks of Cleveland

![]()

|

NOTE: This document was published in 1918. Thanks to Daniel Isom for this significant contribution. |

.

FOREWORD

As the work of the Cleveland Americanization Committee took on more definite

shape, it seemed to separate itself into two divisions; first, bringing the

foreign born residents into close touch with the language, customs and ideals of

America; and second, giving to the native born Americans an understanding of the

racial and political sympathies of the foreign born. Without a common

understanding of the best each has to offer, no real fusion of new and older

Americans will ever take place.

With this end in view, a series of articles has been planned, taking up

individually the various races prominently represented in our cosmopolitan city.

"The Slovaks of Cleveland" is presented as the first of this series. It is very

desirable that this race be better understood in view of the prominent part they

are now bearing in world politics. The establishment of a Czecho-Slovak state

will prove one of the best possible barriers to future German aggression, and

the annals of the Czecho-Slovak army in Russia are full of achievement as heroic

as any the world has ever seen.

The Czechs are well known by their English name, Bohemians, but there is very

little general understanding of the Slovaks. The adjective "Slavish" which is

sometimes used co describe them, has no standing in the dictionary and does not

appear in any ethnological work. Their own adjective "Slovensky" has often led

to their being confused with the Slovenians, who are an entirely different race.

In the census they figure as Hungarians because born in Hungary, and in other

records they appear as Austrians, because they have come from the

Austro-Hungarian monarchy.

It is hoped that this publication may be effective in securing for them a

better understanding.

HELEN BACON, Secretary.

In The northern part of Hungary where the Carpathians slope

toward the great Hungarian plain, is the country called by its children

"Slovensko" or "Slovakland".

Racial Definition. History.

This region, comprising sixteen counties of Hungary, is the home of the Slovaks,

a historic race of solid character and exceeding industry, whose fate through

centuries has been aptly summarized in the statement that they are "the very

step-children of fortune."

It is a rough country, a country of mountainsides and valleys, and has been

inhabited by this same race since the fifth century. In the year 863 the

wonderful story of Christ was brought to the Slovaks by the apostles Cyril and

Methodius. In 870 A.D. their nation came for a brief space into the limelight of

history as the nucleus of the Great Moravian empire under Svatopluk, whose

capital was the city of Nitra. This kingdom was disrupted by Germans and Magyars

early in the next century, and for a thousand years the Slovaks have lived in a

state of vassalage to an alien race, the victims always of oppression and

suppression.

That under these circumstances they have been able to maintain their own

language and their national traditions through so great a period of time

indicates a remarkable tenacity, both mental and spiritual. Their only

fellowship has come from the west,—from their neighbors, the Moravians, and from

the Czechs (here commonly called Bohemians), who live west of the Moravians. The

Moravians and Bohemians use the Czech language. The Slovak tongue, while it is

counted a distinct language, is yet so much akin to the Bohemian that mutual

understanding is easy. This historic fellowship, so long continued, now looks to

find at the end of the present war, political fruition in the establishment of

an independent Czecho-Slovak state.

Hungary is the name of a political division. There are four principal races

within its confines, besides others of less numerical importance. The dominant

race, generally known in America as Hungarians, are from a racial standpoint

more correctly called Magyars. Then there are the Germans, with whom the Magyars

are hand in glove: while the step-children are the Rumanians in southeastern

Hungary, and the Slovaks in the northwestern part.

The Slovaks number more than 2,000,000 souls, possibly even 3,000,000, but this

can only be estimated, as the official census is notoriously unjust to all but

the ruling race. Throughout Hungary there are occasional "islands" of Slovaks,

but probably 2,000,000 at least live in the district called "Slovensko".

Economic Conditions.

This country is, except in certain limited portions, rough and rocky, with

considerable forests. The valleys and fertile lands are mostly owned by the

lords and nobles, absentee landlords all, or by the church, and to these the

peasant must give a certain number of days' work free each year. The roughest

portions, the shallowest soil, the mountainsides, uncultivable to the western

eye, are the farms of the Slovak peasant. In the spring and fall, manure is

painfully, toilingly carried in baskets up the steep slopes to furnish food for

the coming crops.

The prosperous "rich" peasant owns at most a dozen acres, not in one plot but in

strips, of ten miles apart, so that the labor of cultivation is multiplied

manyfold. The poor peasant may try to make a living from a part of an acre.

Failing to succeed in this, he leaves his wife and children to cultivate the

home plot, while he seeks employment abroad, usually as an agricultural laborer

in the plains of Hungary or he may go to the Eldorado, America.

Money the Slovak peasant has only twice a year,—when he returns from this

outside employment and when he harvests his own crops. But he does not have this

long, for the tax-collector takes most of it. If he has been more than usually

unfortunate, and has no money, the tax collector takes his household goods; for

kindness of heart or consideration for the individual or the community does not

influence the tax collector in Hungary.

Food.

The staple foods of the Slovak are black bread, the flour a mixture of barley

and rye, potatoes, cabbage, milk and cheese, and maize meal (corn meal).

Breakfast consists of black bread and a thin corn meal porridge. Dinner is a

soup thick with noodles or vegetables, or cabbage cooked in a rich gravy. If the

soup was made with meat, as happens sometimes, but not often, then the meat is

used as a separate dish. In the better parts of the country, there is a good

supply of such vegetables as beans, peas, carrots, and turnips. Supper usually

consists of potatoes with sour milk, or a corn meal mush with sour milk. Cottage

cheese is much used.

The fruits of the temperate climate, apples, plums, cherries, and apricots, all

are said by the exile to be particularly well flavored in eastern Slovensko, and

wild strawberries abound there. Children gather them and sell them for two cents

a quart. Huckleberries are also plentiful. Sheep cheese, called brindza, is a

favorite article of food, and before the war was imported and sold in a few

Cleveland stores. Mushrooms are much used. Plum brandy and juniper brandy are

home made drinks considered to have medicinal as well as social qualities.

Delicious pastries called kolace and pasky are luxuries to be enjoyed like white

bread, only on occasions such as Christmas, Easter, wedding and christening

celebrations. Meat is always a luxury, and one of the frequent recommendations

given by immigrants to America is that here there is "meat every day". Salt is a

government monopoly, ordinarily sold at ten or twelve cents a pound.

Education.

If the peasant's circumstances are passable and he does not live too far from a

town, he may send his children to school for four winters. The length of this

tetti is determined by agricultural conditions. It is usually from November to

about April, because the children must help to wrest a living from the soil.

Children have to work from an early age, usually from about six years of age and

they do work which we would consider it not only cruel, but impossible to ask

from our children. As one Cleveland child of Slovak parentage has said, "My

father says his children can never know how much better their childhood is than

his was". For their work, children are paid about five dollars a year, and the

day is from sunrise to sundown.

During these four terns of school, the Slovak child will receive instruction in

Magyar,—a foreign tongue, the language, not of his fathers, but of his

oppressors,—a language which the Slovak hates and never uses, except under

compulsion. He says with justice that the Slovak tongue will take him all over

the Slav world, while the Magyar has no value outside of Hungary. Consequently,

the child, studying in a hated language, which has for him no daily use, learns

very little, and finishes his four terms of school almost as ignorant as he

began. It is for him exactly what it would be for us now if our children were

compelled to receive their education in German. Never-the-less, he must in

self-defense learn some Magyar, since he will never be sold a railroad ticket

nor a postage stamp unless he asks for it in Magyar.

A peasant who is both prosperous and ambitious, who is willing to sacrifice what

few comforts he has, and to bend every resource to one purpose, may choose the

brightest of his children for a "higher education". For that the child must be

sent to the city and pay tuition, besides board and other expenses. This can be

done only if the would-be scholar himself seizes every opportunity and creates

opportunities as well, to help himself and to add to the meager allowance from

home. Great is his responsibility. If he should fail, it is failure, not for one

person only, but for all the family hopes.

And from the beginning he must go with an outward acceptance of Magyarization.

The students, Slovak though they may be, are allowed to converse in nothing but

Magyar, even in their most private moments. Always there are monitors whose duty

it is to spy upon and betray their comrades and the school authorities do not

hesitate to search rooms and trunks for such highly incriminating articles as a

little book of Slovak poetry, or a bit of handwriting in that language. Even a

student of theology is likely to be dismissed from the seminary and his whole

career blasted if he shows any interest in the language of his own home and of

his future flock. There is one clergyman in Cleveland to-day who twice saw

fellow students meet this fate and who came to America because he was

"discouraged" in consequence.

Military Service.

After graduating, the student has the privilege of volunteering for military

service, if he does so immediately, and as a volunteer he can go into the army

on terms which make it possible for him to become an officer in the re-serves at

the end of a year. If he does not volunteer, however, he is summoned for service

on the same terms as his brothers, who served for three years from the age of

twenty-one.

The treatment of privates in the Austrian army is unbelievably cruel.

In the first place, the poor Slovak must speak in German whether he knows how or

not. To answer in Slovak is one of the offences which may bring him a slap

across the face, or cruel confinement in the guard-house. Sent to the guardhouse

for some utterly trivial offence like failing to salute perfectly or having his

shoes not shining in the requisite degree, or speaking in Slovak, he may be

given bread and salt to eat and denied water for two or three days. Or his right

arm may be fastened to his left leg with clamps, and he kept in that position

for a day or two. A favorite punishment is to hang him up by a sort of harness

under the aims, drawn up so that his toes barely touch the ground. He will be

kept so until he grows black, then taken down, revived with a bucket of water

and hung up again. Many commit suicide under these punishments.

The soldier's pay is about three cents a day,—hardly enough for the absolutely

required shoe-polish, needles and thread and polish for his brass buttons. He

must have help from home during his whole period of service at a time of life

which ought to be most productive. It is quite obvious that he gains no new

loyalty to his rulers, except that which is instilled by fear.

The Making of Emigrants.

These conditions of political disaffection, of economic difficulty, of

oppressive taxation, with the denial of political representation, of language

and of education, naturally make for emigration, once a goal has been

discovered. The first Slovak emigrants to America, reporting that here they

found "good wages, better living, and free schools, to which any human being can

go" were naturally followed by others, until emigration became for some

districts almost an exodus.

To these people the freedom of America was a discovery almost as great as the

land itself had been to Columbus. What more natural than that they should soon

begin to work toward freedom as a possession of the whole Slovak race. This

desire found united expression in the foillation in May, 1909, of the Slovak

League, whose purpose is to promote the cause of liberty for the Slovaks

everywhere.

Slovak League.

Since the beginning of the great war, this League has actively exerted itself to

direct public sentiment so as to secure for the race just treatment at

the break-up of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy; and to hasten that event by every

possible means. This activity has of course redoubled since the entrance of the

United States into the war, and especially since President Wilson expressed

himself in favor of self-determination of races and governments. "Nove

Slovensko" is a weekly newspaper just started (June, 1918) in Cleveland to

promote the objects of the League.

The Slovaks of this country have wisely joined forces with the larger Bohemian

organization in the fight for racial freedom, and a combination of working

forces has been effected in the organization of the "American Branch of the

Czecho-Slovak National Council". This Council consists of eight delegates each

from the Slovak League and from the Bohemian National Alliance. Mr. John Pankuch

of Cleveland is a member of the Council.

"The Bohemian Review" of March, 1918, makes this poignant statement: "Whereas

Bohemian immigrants in America constitute considerably less than ten per cent of

their race, one-fourth of the whole Slovak people live in America. The Bohemian

National Alliance does not and cannot speak for the Czech nation, for the Czechs

in the old country have their own accredited and regularly elected deputies. But

the Slovaks of Hungary have no elected representatives, and those who emigrated

to America must speak for the whole race". The president of the Slovak League is

Albert Mametej, of Braddock, Pa., secretary, John Jancek, an editor from Russia,

now in Pittsburgh.

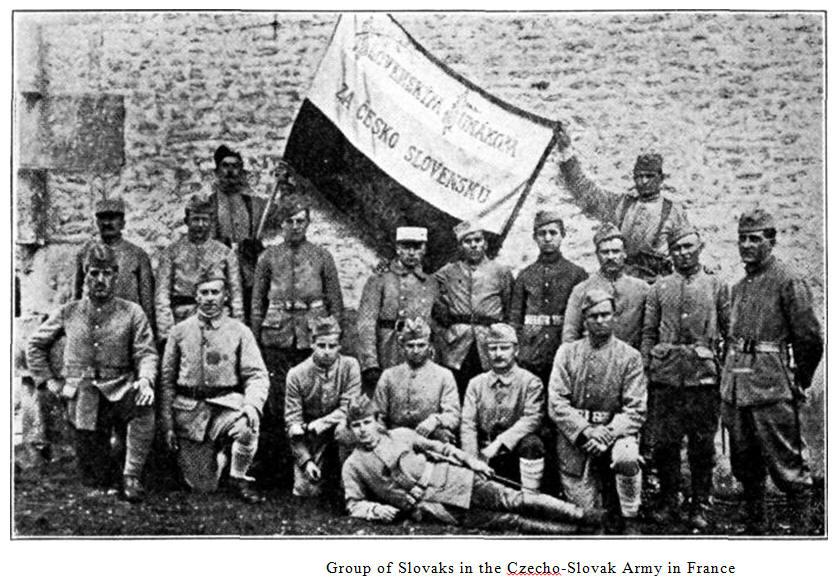

Under the direction of the Council, the Slovaks share in the organization and

maintenance of the Czecho-Slovak army. A recruiting office is maintained in

Cleveland at 5286 Broadway. Men who are not of draft age, or who, because of

their technical classification as alien enemies (being nominally subjects of

Austria-Hungary) are not eligible to service in the United States army, are the

recruits.

This army is trained at a camp in Stamford, Conn., financed by the Council. As

soon as the soldiers embark for France, their expenses are met by the French

government which understands Austria's internal affairs enough to realize, as

our government has not done, that Austria's bitterest foes are those who have

grown up under her sovereignty. In France the Czecho-Slovaks fight under French

officers, but with their own organization, and carrying their own flag. (See

illustration on page 4.)

All Slovaks drafted for service in the United States army have waived exemption,

and they are among the most spirited of our soldiers, since they have not only

the patriotic motives which animate the rest of our army, but in addition a very

vigorous determination to pay off some of the old scores.

Slovak Immigration to America.

The first considerable number of Slovaks coming to America was 1,300 in 1873.

The largest number in any one year was 52,368 in 1905. Cleveland was a

destination for some from 1880, but up to 1886 most of their number settled in

the hard coal region of Pennsylvania, in the districts around Wilkes-Barre and

Scranton. Now they are scattered very widely through the whole United States,

with a few groups in Canada. About half the whole number, however, still is

found in Pennsylvania, with Ohio or Illinois probably second in number, and New

York, New Jersey and Connecticut following.

Slovaktown, Arkansas, is an agricultural community built up by Slovaks who

earned the money for their initial venture in the Pennsylvania coal fields.

Wherever they have settled in this country, the Slovaks have undertaken the

hard, heavy labor, the work fundamental to our great industries. Owing to their

lack of previous opportunity, they have always had to fall into the ranks of the

unskilled, where their dogged indu3try and perseverance have made them valuable,

and their uncomplaining submissiveness has sometimes made them the subjects of

exploitation.

The question naturally arises why more of them do not go to the country, when

practically all were agriculturists before emigration. Two answers are offered

in reply to this question; first, that the weekly pay envelope is irresistibly

attractive to people who had had so little money to handle in the old country;

and second, that in the city, the women also can work.

Among the Slovak immigrants, it has been very usual for the man of the family to

come first, often not intending to stay permanently. It was to him simply a

greater migration than the former habitual one to the plains of Hungary. Miss

Balch shows in "Our Slavic Fellow-citizen" pictures of "American" homes in

Slovensko, built by returned emigrants with the proceeds of American toil. Many

others, however, have on return found themselves so changed as to be out of

place in the old surroundings. An "American", returning to Hungary, is a thorn

in the flesh to the officials, to whom he no longer doffs the hat nor kisses the

hand. In consequence, passports for the second trip are often obtained more

easily than they were for the first, and the man who went home to stay, shortly

severs all ties and brings his family to America with him.

Others, without the experience of returning, analyze things for themselves and

conclude, "Why should I go back?"

After the War.

When the war comes to an end, there will however be a great exodus, caused by

the desire for immediate and accurate news of relatives, friends and homes from

whom the separation has been complete for so long. There are in Cleveland more

than 600 Slovak men whose families in Hungary were dependent upon remittances

from this country. The agonizing situation of these men, so long without news

and with so little reason for hope, is such as to make them subjects for the

keenest sympathy. It is safe to say that there is hardly a Slovak in Cleveland

who has not mother, wife, children, or sisters in the old country, and who will

not wish to see with his own eyes what the war has done to them. How long he

will stay depends upon economic and political conditions which it is impossible

now even to forecast.

Distribution of Slovaks in the United States.

The distribution of Slovaks in the United States is a subject on which it is not

possible to present any figures, as the census records do not indicate the race,

but count them in with all the other emigrants from Hungary.

Two methods of approximation of local populations are available: first, the

records of the Slovak churches in the United States; for the Slovaks are a

religious people, and there are comparatively few without a church connection.

Second, the records of the various societies, mostly beneficiary, which are

organized on a nationalistic basis; that is, only persons of Slovak ancestry are

eligible.

The establishment of a new Slovak church obviously means the presence of a

number of Slovaks sufficient in means and interest to buy property and to

maintain an institution. Similarly, the formation of a branch, or "lodge", of a

fraternal organization indicates the existence of a group able to meet and pay

dues, and desirous of receiving the benefits of the organization.

Distribution of Slovaks in Ohio.

The distribution of Slovaks in Ohio is indicated by the following list of towns

which have branches of one or more of these societies:

| Adena | Belle Valley | Cambridge | Congo |

| Amsterdam | Berea | Canton | Conneaut-Jester |

| Ashtabula | Black Top | Castalia | Danford |

| Ava | Bradley | Cincinnati | Dayton |

| Barberton | Buffalo | Clay Center | Dillonvale |

| Barton | Byesville | Cleveland | Dover |

| Bellaire | Caldwell | Coalridge | East Toledo |

| Fairport | Lorain | Murray City | South Lorain |

| Glencoe | Lowellville | Neffs | Steubenville |

| Gypsum | Lucasberg | Pine Fork | Stewartsville |

| Haselton | Mansfield | Pleasant City | Struthers |

| Hubbard | Marblehead | Port Clinton | The Plains |

| Kelley's Island | Martin's Ferry | Ramsey | Toronto |

| Kipling | Massillon | Rhodesdale | Walkers |

| Klondyke | Maynard | Robins | Wolf Run |

| Laferty | Middletown | Rossford | Wheeling Creek |

| Leetonia | Mingo Junction | Roswell | Yorkville |

| Lore City | Moxhala | Salem | Youngstown |

Cleveland became a goal for Slovak immigrants as early as 1880. Jacob Gruss

(see illustration on page 18), who with his wife came to America in that year,

was advised by a Bohemian employment agent in New York, to proceed to the mining

regions of Pennsylvania. Mr. Gruss preferred to work above ground, so the agent

said, "Why not go to Cleveland ? That is a new city, with lots of work."

Arriving here, Mr. Gruss, who now lives at 9627 Stoughton Avenue, found one

fellow countryman, a man named Roskos, already here. In 1881 a few more Slovaks

came to Cleveland, in 1882 a larger number.

"The Father of the Slovaks."

In March, 1882, arrived the Rev. Stephen Furdek, the first Slovak priest in

America. By a curious turn of fate, he came, however, to minister to the

Bohemians. Bishop Gilmour, of the Roman Catholic diocese of Cleveland, had

written to Prague for a priest for his rapidly increasing number of Bohemian

parishes, and Father Furdek, although a Slovak, only 24 years of age, and barely

through his theological studies, was chosen to answer the call. He arrived here

in March, 1882, and was ordained to the priesthood July 2nd, in St. Wenceslaus

Bohemian church, of which he became the pastor. Two years later, he was given

the task of organizing the new Bohemian parish of Our Lady of Lourdes, which

soon became the largest Bohemian parish in the city, and where he remained until

his death, Jan. 18, 1915.

While successful to the highest degree in his appointed work among the

Bohemians, Father Furdek was a man of such breadth of interest, of such large

ability, and of so much executive talent, that he was able from the first to act

also as a leader of the Slovaks. Becoming first the friend and counsellor of the

few whom he found already in Cleveland, his interest grew and broadened until he

became a national figure, and was everywhere affectionately known as "The Father

of the Slovaks."

Slovaks in Cleveland.

There is no official record which will show the growth of our Slovak population,

but in a general way it can be estimated and localized by reference to the

history of the Slovak churches of our city. By following their development, it

is possible to learn in what parts of the city Slovak centers have developed,

and at what time each new community has increased to the point of forming a new

religious organization.

In 1885 Father Furdek began holding Slovak services regularly in the chapel of

the Franciscan Brothers on Woodland Avenue, and so brought together into a

religious body the little group of Slovaks in Cleveland at that time.

These first Slovaks had settled in the district around Hill,

Berg, Commercial, and Fourth Streets, but Father Furdek urged very strongly that

they find a more desirable location for their permanent home. Through his

influence a location was chosen in what was then the outskirts of the city,

along Buckeye Road and parallel streets from about East 78th Street to Woodhill

Road. Here the settlement rapidly grew, the Slovaks building small, neat

cottages.

In 1887, the collection of funds for a church was begun, and an organization was

effected Dec. 2, 1888. As there were Magyars living in the same neighborhood and

also in need of a church, an attempt was made to combine the two interests, and

the parish was named for the Magyar saint, St. Ladislas. It was not long before

difficulties began to arise between the two races, and eventually great

bitterness developed. The ensuing contest was settled by the Bishop, who decreed

that the Magyars should build themselves a new church, and that the Slovaks

should pay them $1,000 for their interest in St. Ladislas.

In recent years this neighborhood has changed very much, and the small homes of

the Slovaks have been largely crowded out by tenements, so that sixty-five per

cent of the original population have now moved farther out.

New property has been acquired on East Boulevard, at the foot of Sophia Avenue,

where it is planned first to erect a new school building, to be followed later

by a new church and other parochial buildings. The present parochial school

houses about 700 children, who are taught by the Sisters of Notre Dame..

Holy Trinity Evangelical Congregation.

The next Slovak parish organization was a Protestant one, the Holy Trinity

Evangelical Lutheran Congregation, founded Dec. 5, 1892. This was the third

Slovak Lutheran parish in the United States, the first having been in Freeland,

Pa.

Holy Trinity parish was established in the down town district, and although the

character of the local population has entirely changed several times, the

original location still seems most convenient to this congregation. The church

is at 2506 East 20th Street, where the parishioners find it easy to come from

all over the city.

There is a parochial school where two teachers give instruction to 65 children

in the work of the first four grades. For more advanced work, the children go to

the public schools, and attend special instructions in religion and the Slovak

language four hours a week in the parochial school. Additional property has

recently been acquired to furnish a playground for the children of the school.

While this church is one of the oldest Slovak organizations in the city, it is

an interesting fact that about half of the present congregation are immigrants

of the past six or eight years.

The pastor, Rev. Alexander Jarosi, is a Slovak from southern Hungary. Educated

in a Hungarian university, his coming to America was due to the fact that at the

very moment when he was feeling most bitterly the governmental oppression of his

native land, he received a letter from America telling him of the great need for

Slovak ministers here. Mr. Jarosi is keenly interested in assisting the men of

his congregation to become American citizens, and deplores the fact that so far

his Hungarian birth and his rank as an officer in the Austrian army, have caused

the refusal of his various applications for service in the United States army.

St. Martin's Church.

In the same neighborhood as Holy Trinity Church, the Roman Catholics founded St.

Martin's Church two years later, in 1894. This was first located on East 25th

Street; in 1902 a church was built on East 23rd Street, and in 1907 a larger one

was erected at the corner of East 23rd and Scovill Avenue. The old church is

used as a school building, and three dwelling houses have also been altered into

school rooms. Five hundred and fifty children are enrolled, the teachers being

the Sisters of St. Joseph. Two young men from this parish are now studying for

the priesthood.

The development of these three parishes may be taken to indicate the character

and location of the first phase of Slovak immigration to Cleveland.

Nationalistic Societies.

During this period from 1880 to 1894 the Slovak population of the United States

increased in very much the same proportion as did the Slovak population of

Cleveland, and in 1890 sufficient impetus had been gained to lead to the

establishment of the first of the nationalistic societies which are so large a

feature of Slovak life in America.

National Slovak Society.

February 16, 1890 marked the beginning of the movement. On that date was

organized in Pittsburgh under the leadership of P. V. Rovnianek, "The National

Slovak Society of the United States of America." (Narodny Slovensky Spolok v

Spojenych Statoch Americkych). Its aims, as stated in the "Constitution and

By-laws, 1916," are:

"To educate the Slovak immigrants, who, being victims of unfavorable political

conditions in their own country, were deprived of the means of education and

culture; to make of its members all sons of their nation; to teach them to love

their adopted country and to become useful citizens of this Republic; to help

one another in sickness and distress and to help the widows and orphans when

their breadwinners have passed away."

The duties of members as defined by the By-Laws, include the following: "He must

lead a moral life, make an honest living, and refrain from acts which would

bring disgrace upon the National Slovak Society, and dishonor to the Slovak

race." "It shall be the duty of every member to become a citizen of the United

States within six years after his admission to the Society. If he neglects to do

so, a complaint shall be filed against him in the Supreme Court."

Five "funds" are maintained: Mortuary fund, for the payment of death benefits;

administration fund, for the running expenses of the organization; indigent

fund, for the relief of disabled members who have exhausted the benefits to

which they are entitled from their local societies, but who are in extreme want;

a national fund, for "the moral development and for the uplifting of the honor

and good name of the Slovak nation"—from this students may be educated and

national purposes promoted; an orphans' and old folks' home fund.

The official motto of the society is "Freedom, Justice, Brotherhood." It has 700

branches, widely distributed throughout the United States and Canada, with

42,259 members, and 7,500 junior members. 6,513 members have died, and their

beneficiaries have received $4,527,804.96. Sickness and accident benefits paid

have aggregated $85.228.86. The present capital is $1,870,869.56. Albert

Mametej, Braddock, Pa., is president and Joseph Durish, Pittsburgh is secretary.

"Narodny Noviny" (National News) a weekly newspaper, is the official organ of

the society. The Literary Committee is a standing committee of the society,

whose duty it is to provide for the publication of useful books for the members.

First Catholic Slovak Union.

On the fourth of September of the same year, another society of similar aims was

started in Cleveland by the Rev. Stephen Furdek. The first convention was held

in the home of Jacob Gruss, and was attended by eleven delegates (see

illustration on this page.)

This society was called the First Catholic Slovak Union (Prva Katolicka

Slovenska Jednota) and its membership is limited to Roman Catholics or Greek

Catholics in good standing. Its headquarters are in Cleveland, where the

secretary has a suite of offices in the Guardian Building.

"Every member of this Union shall become a citizen of the United States within

six years after his arrival in this country, and as a true son of the Slovak

nation he shall cultivate the Slovak language and nationality inherited from his

forefathers, preserve it for coming generations, and thus become worthy of his

ancestors." (Extract from the Constitution.)

The first Catholic Slovak Union now has a membership of 50,049

with 19,690 junior members. It has paid out in benefits $5,000,000 and has a

capital of $1,532,671.49. The capital of the junior society is $57,513.21. A. J.

Pirhalla, Duquesne, Pa. is president, Michael Senko, Cleveland, secretary.

The distribution of branches is as follows:

| Pennsylvania | 302 | Minnesota | 6 | Arkansas | 2 | ||

| Ohio | 72 | Missouri | 6 | Wyoming | 2 | ||

| Illinois | 55 | Colorado | 6 | Louisiana | 1 | ||

| New York | 33 | Maryland | 4 | Georgia | 1 | ||

| New Jersey | 29 | Washington | 3 | Oklahoma | 1 | ||

| Connecticut | 20 | Maine | 3 | New Mexico | 1 | ||

| Wisconsin | 13 | Montana | 3 | Virginia | 1 | ||

| Michigan | 12 | Massachusetts | 3 | Alabama | 1 | ||

| West Virginia | 9 | Kansas | 3 | California | 1 | ||

| Indiana | 7 | Iowa | 2 | Canada | 7 |

"Jednota" (Union), the official publication, was started by

Father Furdek as a small sheet in 1890, and was edited in Cleveland continuously

for the first ten years, and intermittently since, the annual convention

determining the place from year to year. It is a weekly paper, taken by all

members, and is now published in Middletown, Pa.

The Catholic Slovak Ladies' Union.

This is a society for men; the Slovak women were no more to be outdone than

their American sisters would be, so they founded in January, 1892, "The Catholic

Slovak Ladies' Union" (Katolicka Slovenska Zenska Jednota). The organization and

by-laws are like those of the brother organization. They have capital to the

amount of $429,049.48, of which $240,000 has been invested in Liberty Bonds.

There are 388 branches, having a total of 26,044 members, with representation in

26 states and Canada.

The headquarters of the Union are in Cleveland, where Mrs. Anna Ondrej, 3134

East 94th Street, is national president, and Mrs. Maria E. Grega, 9619 Orleans

Avenue, is general secretary. The official organ "Zenska Jednota" (Ladies'

Union) is edited and published at 5103 Superior Avenue by the chaplain, Rev.

John M. Liscinsky.

The Slovak Evangelical Union.

Naturally the next organization to be founded was of the opposite religious

faith, the Evangelical. The Slovak Evangelical Union (Slovenska Evanjelicka

Jednota) was founded in Freeland, Pa. in 1893. Its objects also are fraternal.

Its capital is $230,225; it has paid out in death benefits for men $741,674; for

women $77,755; for accidents, $43,399. It has 199 branches, and 58 junior

branches, 10,584 members.

Its headquarters are now in Allegheny, Pa. The president is Jan Matta,

Brownsville, Pa.; secretary Jan B. Bialek, 1601 Beaver Ave. Pittsburgh.

Its official publication is Slovensky Hlasnik (Slovak Herald) published weekly

in Pittsburgh. This also serves as organ for the sister society, the Evangelical

Slovak Ladies' Union.

The Evangelical Union has been unfortunate in the matter of unity, and an

offshoot from it is the National Slovak Western Union, with headquarters in

Chicago, and the Evangelical Slovak Union, founded in 1909 in Cleveland, of

which John Pankuch of Cleveland is president and Stevan Alusie, of 1928 Mead

Avenue, Racine, Wis. is general secretary.

Cleveland Slovak Union.

A local organization along the same lines but non-sectarian in membership is The

Cleveland Slovak Union, founded in 1899. It has in Cleveland 26 branches, with

1367 members and a capital of $49,485. The main society pays death benefits

only, the branches pay also accident and sickness benefits. The president is

George Putka, 2626 East 130th Street.

The objects of the Cleveland Slovak Union are stated as follows: "To educate the

Slovak people, who have been deprived of the privilege of education by

unfavorable circumstances in their fatherland; to foster intelligence among the

members, to teach them to love the new fatherland, and make useful American

citizens of them; to support the widows and orphans in case of the death of

members."

Sokols.

Another motive, that of physical culture and training, is a prime object in the

Slovak Gymnastic Union Sokol (Telovicna Slovenska Jednota Sokol). This had on

May 1st, 1918, 10,838 members, most of the chapters being in the states of New

Jersey, New York, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, Ohio and Illinois.

Its headquarters are in Perth Amboy, New Jersey, where it was organized July

4th, 1896. The president is Stephen Erhardt, Bridgeport, Conn., the secretary

Frantisek Stas, Perth Amboy.

"Slovensky Sokol" (Slovak Falcon) published semi-monthly at 1424 Vyse Ave. New

York, keeps the members in touch with the organization.

"The Roman and Greek Catholic Gymnastic Slovak Sokol Union" (Rimsko a Gr.

Katolicka Telovicna Slovenska Jednota Sokol) is a similar organization limited

to a Catholic membership. It was organized in 1905 in Passaic, N. J., has 15,000

members, $100,000 capital, and owns a printing establishment valued at $15,000.

Its publications are "Katolicky Sokol," weekly, and a monthly juvenile

periodical, "Priatel Dietok".

Each of these national orders has many branches and hundreds of members in

Cleveland, and it is doubtless due to their beneficiary features in addition to

the natural thriftiness of the race that the number of Slovaks who appear as

applicants for charitable aid, is extremely small.

The great danger seems to be that an individual may take out membership in more

societies than he can afford to carry.

The meeting places of these various "lodges" are often in the parochial school

buildings, or in rented halls equipped for that purpose.

Slovak National Home.

The "Narodny Slovensky Dom" (Slovak National Home) Corporation erected in 1906 a

building at 8804 Buckeye Road to serve as a general center for Slovak

organizations and activities. Its management has unfortunately not been entirely

successful, and its ownership is now vested in M. N. Soboslay, a prominent

Slovak, who regards it as held in trust for its original purposes.

Second Stage of Growth.

The second stage in the growth of Cleveland's Slovak population is indicated by

the fact that at the end of ten years, the three churches already described, St.

Ladislas, Holy Trinity, and St. Martin's, were no longer sufficient to care for

the needs of the race, and a new era of church building set in.

St. Wendelin's Church.

A settlement had grown up on the West Side, which was formed in May, 1903, into

the parish of St. Wendelin. The original settlement was in the district bounded

by West 17th and West 22nd Streets, Lorain Avenue and Columbus Road. More

recently the Slovaks have moved into the old Lincoln Heights neighborhood,

between West 5th and West 11th Streets. There are also about 80 Slovak families

near Denison Avenue.

The present church of St. Wendelin was built in the year of the parish's

organization, and has for some time been inadequate to the needs of the greatly

increased membership. Property has been purchased at Columbus Road and Freeman

Avenue where new buildings will be erected after the war. The parochial school

of St. Wendelin has 900 pupils, the teachers belonging to the Sisters of Notre

Dame.

St. John's Church.

In 1905 the parish of St. John on West 11th Street was founded. It has so far

had a checquered history, due to a lack of approval on the part of the Roman

Catholic bishop of the Cleveland diocese. It is now affiliated with the

Independent Diocese of Scranton, Pa. under the Right Reverend Francis Hodur, and

has a settled pastor in the person of the Rev. Stephen Vincent Tokar, a young

American, the son of Slovak parents, born in Pennsylvania.

A fine church building is just about to be begun, and the parish seems to be on

the threshold of a brighter future.

Nativity Church.

The same influences of industrial opportunity and increased immigration which

led to the establishment of St. Wendelin's, had also been the occasion of great

growth at St. Ladislas, and the extension of its territory to an unwieldy

extent. As a result, the parish of St. Mary of the Nativity was formed in 1903.

This is east of the Newburg plant of the American Steel and Wire Company, in the

neighborhood of East 93rd Street and Aetna Road. While conveniently near the

mills for the men who are employed there, the land is so much higher that the

air is clean and clear. It is a district of home owners, of comfortable single

or two-family houses, neat yards and well tilled gardens. Its orderly

development has been inspired since 1909 by a pastor who is a true shepherd of

his flock, the Rev. V. A. Chaloupka.

This year the spirit of neighborhood improvement was so general that over 6,000

ornamental shrubs were set out, besides small fruit and shade trees.

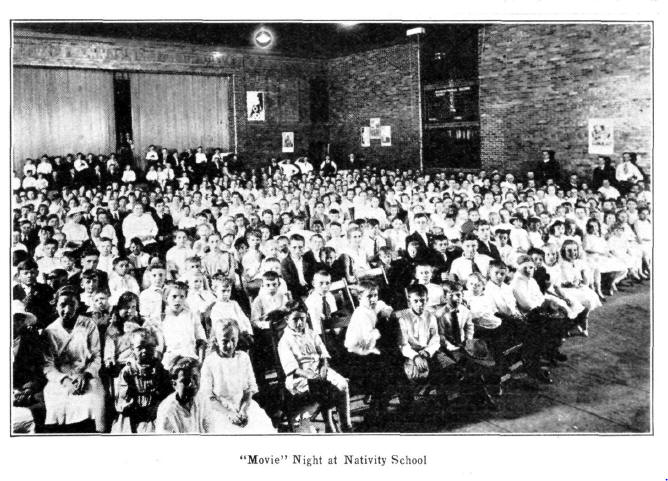

The Nativity school building erected in 1916, is built according to the most

improved models, and possesses features which make it a genuine community

center. Its large auditorium, which seats 800, is in use every Sunday evening,

and often during the week. Sometimes the dramatic club gives a play, sometimes

there is a lecture on some topic of the hour, sometimes a dance with an

attendance of 250 couples, but oftenest the entertainment provided is moving

pictures. Father Chaloupka chooses the films, and intersperses the instructive

with the merely entertaining. One night last winter 1,100 people enjoyed moving

pictures depicting religious scenes.

The bowling alley is a feature of the school building much appreciated by the

young men of the neighborhood, and the women have classes in the various

branches of domestic science and in Red Cross work.

Night school classes in English and citizenship were held last winter under the

direction of the Americanization Committee, Father Chaloupka having himself

previously taught citizenship classes, also acting as witness for his men in

naturalization court.

St. Andrew's

Church.

The youngest Roman Catholic Slovak church in the city is Sc. Andrew's on

Superior avenue, near East 55th street. This also is to some extent an outgrowth

of St. Ladislas parish, many of the families having moved to this neighborhood

because of its nearness to their employment in the various large manufacturing

plants north of Superior avenue, on Lakeside avenue, and along the Nickel Plate

tracks. They are buying homes in the neighborhood as fast as the former

residents are willing to sell . . This parish was organized in 1906, the church

was dedicated in 1907. Rev. John M. Liscinsky, who has been rector since 1908,

has the distinction of being the only Roman Catholic priest in the city who is

Slovak born, the others being Bohemians and Moravians.

Martin Luther Evangelical Congregation.

The Martin Luther Slovak Evangelical Lutheran Congregation was founded in 1910,

and used a dwelling at 2139 West 14th St. as a church until 1917. The

four-hundredth anniversary of the Reformation was celebrated by this

congregation with the opening of their new church. The structure is of red

brick, very pleasing in style. The Slovak Protestants trace their history back

to the refoillation of John Huss, so in the decorations of this church the

coat-of-arms of Martin Luther is balanced by "The Cup", the emblem of the

Hussites.

Rev. Albert D. Dianiska, the pastor, is a Slovak, whose father and grandfather

before him were Lutheran ministers. Mr. Dianiska has in his library manuscript

volumes of devotion which they used in the dark days of religious persecution,

in Hungary when meetings could be held only in secret, and printed books were

not available.

Greek Catholic Church.

In a religious survey of the Slovaks, consideration must also be given to the

Greek Catholic Church. This is a church whose existence is hardly known to

Americans, much less understood by them. It is a result of the efforts of the

Roman Catholic Church to convert the Greek Orthodox Russians. In the year 1595,

this effort reached a degree of success among the Little Russians (or

Ukrainians), who consented to acknowledge the supreme headship of the Pope, and

to accept the filioque clause in the creed, on condition of being allowed to

retain various practices of the Eastern Church. They retain the mass in Slavonic

instead of in Latin, the Eastern arrangement of the church, with the great gilt

screen in front of the altar, the communion in both kinds to the laity, the

married clergy, the Eastern form of the cross, with three cross-bars, the lowest

oblique, the Cyrillic alphabet, and the calendar thirteen days behind the Roman.

Most of the Little Russians are Greek Catholics; so also are those of the same

race who live across the border in Galicia and in the adjoining part of northern

Hungary. In Hungary this race is called by various names; perhaps Ruthenian is

the best known. They are a Slav race, akin to the Slovaks, who adjoin them on

the west. It is quite natural that where they meet and mingle, there should be

mingling of religious faiths. Consequently a considerable number of Slovaks are

Greek Catholics, but it is very difficult to get accurate information on the

subject, so far as Cleveland is concerned.

It is noticeable that in every Slovak community there is a Roman Catholic

church; then later a Greek Catholic church is formed in the same neighborhood.

St. John the Baptist Greek Catholic Church on Scovill Avenue, which has recently

gone over to the Greek Orthodox communion, and the Church of the Holy Ghost on

Kenilworth Avenue near West 14th Street are undoubtedly made up in part of

Slovaks. St. Joseph's Greek Catholic Church on Orleans Avenue near East 93rd is

almost entirely Slovak, while it is probable that other churches of that faith

have some representatives of the race.

These Greek Catholic Slovaks are most unfortunately situated in this country,

since it is very difficult for them to obtain any clergy. They must accept

clergy who are either Magyar or Ruthenian, and the consequence at present is a

great amount of dissension. It seems a far cry from Ukrainia's peace treaty with

Germany to a church quarrel in Cleveland. But the connection becomes apparent

and urgent when the priest calls himself a Ukrainian with all that that may

imply as to political sympathies; while the parishioners are devoted heart and

soul to the Czecho-Slovak cause and do not hesitate to call Ukrainia's separate

peace a treason to the general cause.

There are several Protestant missions among the Slovaks. The Baptists have two,

of which the larger has a neat church building at College and Tremont Avenues,

the pastor of which, the Rev. Paul Bednar, is himself a Slovak. There are

without doubt also Slovak members in every Protestant Bohemian church in the

city.

Present Day Statistics.

Having surveyed the growth and location of Cleveland's Slovak population as

indicated in the history of the Slovak churches, we may take the church

statistics as the only existing basis for a computation of their numbers at the

present day.

The Roman Catholic clergy record the size of their parishes by the number of

families, and then estimate the number of individuals usually by figuring five

persons to a family. The Lutheran pastors record the actual number of

contributing members, which may be taken to mean usually heads of families. Five

is a very conservative figure to use as a multiple, since Slovaks all have large

families, ten or twelve children being not at all unusual.

The figures thus obtained make the number of Slovaks in Cleveland about 35,000

as follows:

| St. Ladislas' Parish | 4,000 |

| Holy Trinity Parish | 2,500 |

| St. Martin's Parish | 3,500 |

| St. Wendelin's Parish | 5,000 |

| St. John's Parish | 2,500 |

| St. John the Baptist Parish | 3,500 |

| Nativity Parish | 2,500 |

| St. Andrew's Parish | 2,000 |

| Martin Luther Parish | 3,000 |

| St. Joseph's Parish | 1,000 |

| Other churches | 3,500 |

| No church connection | 2,000 |

| Total | 35,000 |

The location of these churches indicates the principal

centers of the race in Cleveland. The different neighborhoods show the

variations incident to the length of residence in this country and

consequent financial condition. All Slovaks have come here poor and

industrially unskilled, and the first generation can seldom do more than

establish the family economically. Their children must work as soon as they

are able and help to secure the family's financial footing. This includes

always the ownership of a home, the purchase of property being particularly

satisfying to the Slovak because it is something he could never have hoped

for in the old country. The percentage of home owners varies from about

one-third in some districts to over three-fourths in others.

Three Slovak building and loan associations assist in the acquisition of

property. They are:

The Tatra Savings and Loan Association ............................. 2437

Scovill Ave.

The First Slavonian Mutual Building and Loan Association ... 9722

Buckeye Rd.

The Orol Building and Loan Association . ........................ 12509

Madison Ave.

Slovaks in Industry.

While the location of their churches indicates the principal centers of the

race in the city, the original determination of that location was usually

due to its accessibility to manufacturing plants offering employment in the

kind of work which Slovaks are best able to do. The Slovak of Cleveland,

like the members of his race elsewhere, furnishes the fundamental heavy

labor for many of our largest industries. They constitute a large proportion

of the pay-roll in such plants as the American Steel and Wire Company, the

Corrigan-McKinney Co., the Cleveland Hardware Co., the Ferry Cap and Screw

Co., the National Carbon Co., the Mechanical Rubber Co., and the Upson Nut

Co. Their homes are therefore located in districts from which they can

easily reach these plants.

Many of the young women work in cigar and candy factories.

Slovak Citizenship.

As soon as the Slovak has decided to make this country his home, he takes

out "citizen" papers and becomes an American. His doing so is stimulated by

the regulations of the fraternal society to which he belongs and by his

pastor.

The clergy of the Slovak parishes in Cleveland are entitled to great credit

for the influence which they exert in behalf of Americanization. Several of

them have personally conducted citizenship classes, taking their men to the

court for examination; while others have exerted their influence to have

their men take advantage of existing agencies in schools, libraries, etc.

This year (1917-18) classes in English and citizenship were conducted

under the direction of the Americanization Committee, in the parochial

schools of St. Wendelin, St. Ladislas, and Nativity, and in the church of

the Holy Ghost.

At St. Wendelin's a kindergartner was provided to take care of the little

children of the mothers who attended.

At least one-third and in some districts a much higher percentage of the

Slovak men are American citizens.

Slovak Publications in Cleveland.

Intelligent citizenship is greatly assisted by local newspapers in their own

language. "Dennik Hlas" (Daily Voice) and the weekly edition "Hlas" extend

to all Slovaks the sturdy Americanism and the true patriotism of the editor,

Mr. John Pankuch, who is known among Slovaks throughout the United States.

It is published at 634-638 Huron Road.

"Nove Slovensko", published at the same address, under the editorship of

Ignace Gessay, is devoted to the interests of the Slovak League.

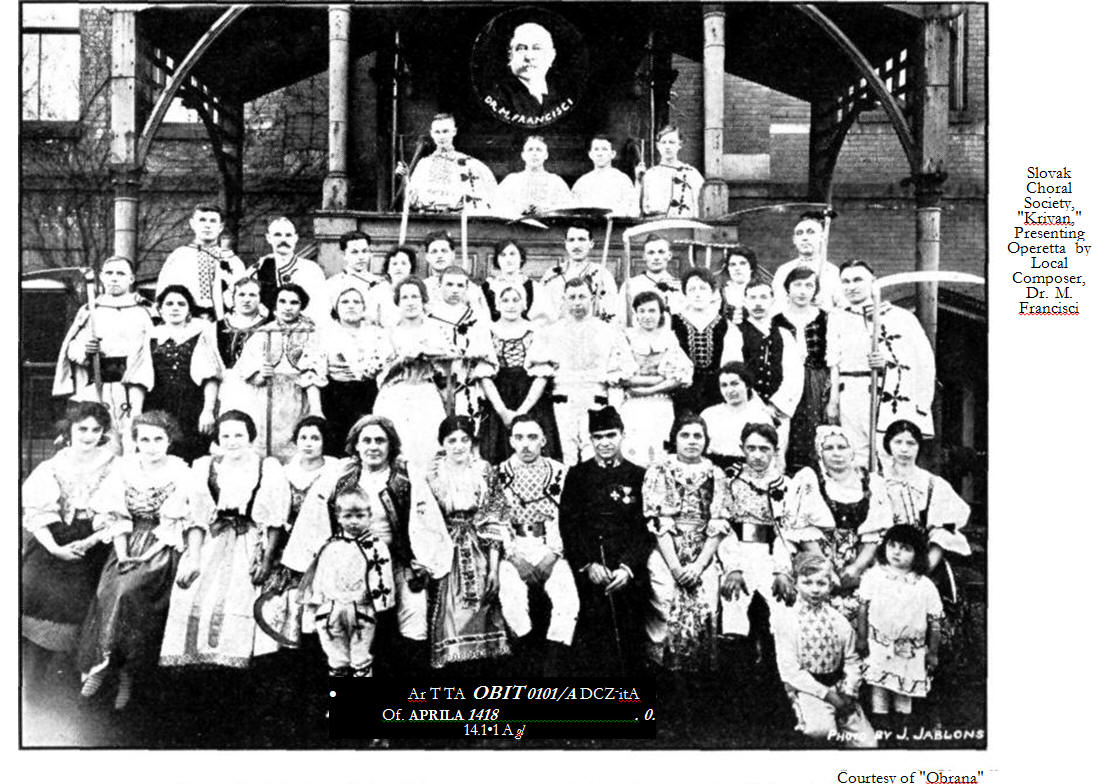

"Zenska Jednota", (Woman's Union), a semi-monthly, and "Obrana" (Defense),

an illustrated periodical, are published at 5103 Superior Avenue by the Rev.

John M. Liscinsky.

The following books in Slovak have been published by Cleveland authors. The

list is doubtless incomplete. The Americanization Committee will be glad to

receive additions to the list:

Furdek, Stephen . . . Kde se vzal svet? 160 pages, illustrated.

Furdek, Stephen. Svet a jeho zahady. 1910. 249 pages, illustrated.

Furdek, Stephen. Slovak text books for use in Slovak schools.

Horvath, Frantisek.... Sbierka slovenskych piesni. (Slovak songs with

music.) published in Leipzig.

Marshall, Gustav (pseud-Petrovsky). Abrahamova obet ; trans¬lated from the

Dutch of Gustav Jansson.

Marshall, Gustav (pseud-Petrovsky). Z pcd zanejov Arnerickych.

Salva, Karol Tovarysstvo. 3 volumes.

Konig, Janko and Pankuch, Jan Slovensky humoristicky kalendar pre americkych

Slovakov na rok 1915.

Wolf, Antoin. Hlupy Janko.

Other Slovak Publications.

Other Slovak publications of general interest are:

"How to obtain citizenship" in English and Slovak; "Slovensko-Americky

vencek" (Slovak-American song-book).

"Slovak-American Interpreter. Novy Anglicky Tlumocnik pre Slovakov v

Amerike".

These are all publications of the Slovak Press, 166 Avenue A., New York.

Dixon, Charlton Slovak grammar for English speaking students.

Mametej, Albert.Novy Americky tlurnac. (New American Interpreter).

These were both published by Rovaianek in Pittsburgh in 1904.

Kadak, P. K.. Obrazkove dejiny Ameriky (History of the United States).

Scranton, Pa. 1908.

Nyitray, Emil. Slovensko-Anglicky a Anglicko-Slovensky vackovy slovnik.

(Slovak-English pocket dictionary).

Mr. M. N. Soboslay has a Slovak book store at 9722 Buckeye Road, where he

carries books in that language from all over the world.

Public Library.

The Cleveland Public Library has 450 Slovak books, which are in constant use

among the Slovaks of the city, many of whom also read the larger collection

of Bohemian books in the Library.

Slovak Education in America.

The Slovak, who had so little opportunity for education in his own

childhood, appreciates very highly the facilities open to his children in

the schools of this country. It is seldom financially possible for him to

send them farther than the-grammar grades in the first years of life in the

new country, but of course that represents a great gain over what would have

been possible in Hungary. With the acquisition of homes and comfortable

living conditions, the number of children in high school increases very

rapidly. A good many have graduated from business schools, and gone into

office work instead of following their fathers into the factory.

There are as yet only a few professional men among the Slovaks: The

following are apparently the only ones:

J. C. Ferencik, and Gustavus C. Gilbert, attorneys.

M. Francisci, a physician at 3242 Lorain Avenue, and Dr. John A. Filak, now

in the United States service. Dr. Francisci is also widely known as a

musician and composer.

The Slovak as an American.

As a member of the community, the Slovak has in a high degree those

qualities of character which make the solid substantial citizen. He is

nat¬urally conservative, and not inclined to seek changes in the social

order, therefore he has an extremely small representation among the

Socialists, and is never an agitator. Rather his disposition is always to

make the best of things as he finds them. He is simple, direct,

straightforward. The word subterfuge has no equivalent in his language. He

is industrious in a patient, plodding way. In his own country, he worked to

an accompaniment of song. A field of agricultural laborers would sing

folk-songs together as they worked, songs in a minor key, breathing patience

and resignation. Here he is sometimes confused by the speeding-up process,

but adapts himself to it with the same spirit of patient resignation, but

alas, with no opportunity for song.

He buys property, and thus early becomes a tax-payer. He becomes a citizen

and a voter; as yet he has had no desire to share in the machinery of our

political parties, but his understanding of the issues involved in an

election is probably equal to that of the average native-born.

As he cultivates his flourishing "war-garden", he wonders if his friends and

relatives back in Hungary are having anything at all to eat, and he puts all

his soul into the making of the munitions which are to free them from the

yoke of centuries.

Ask one hundred Slovaks why they came to America, and two or three will say

that they came "to see what it was like", while the other ninety-seven or

ninety-eight will promptly give you these three reasons: "To make a better

living, to educate my children, to live under a free government."

Surely these are the best ideals that we can ask of any immigrant.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Balch, Emily

G.............................................................................

Our Slavic fellow-citizens.

Capek, Thomas.

............................................................................The

Slovaks of Hungary.

Jamarik, Paul........................ Hungary and the future peace

terms;pub. by the Slovak League.

Kulamer, John. ........................................The Life of John

Kollar; pub. by the Slovak League.

Mamatej, Albert..The situation in Austria-Hungary; a reprint of an article

in the Journal of Race

Development. Oct. 1915.

Rovnianek, P. V ........The Slovaks in America. (In Charities, v. 13: p.

239-245, Dec. 3, 1904.)

Seton-Watson, R. W

.................................................................Racial

problems in Hungary.

Steiner, E. A

.............................................................The Immigrant

Tide; its ebb and flow.

p. 93-101. The doctor of the Kopanicze.

p. 124-138. The disciples in the Carpathians.

p. 215-226. The Slav in historic Christianity.

United States Immigration Commission...........................Dictionary of

races or peoples, 1911.

(Article on the Slovaks, p. 132.)

Slovak Newspapers and Periodicals

Published in the United States.

Daily

Dennik Slovak v Amerike...............................................166

Ave. A, New York

Narodny Dennik .............................................4th & Penn Ave.,

Pittsburgh, Pa.

New Yorksky Dennik ............................................502 East 73rd

St., New York

Denny Hlas...................................................... 634-638

Huron Rd., Cleveland

Semi-weekly

Slovak v Amerike.........................................................

166 Ave. A, New York

Weekly

Amerikansko-Slovenske Noviny.............................. 4th & Penn Ave.,

Pittsburgh

Jednota.................................................................................

Middletown, Pa.

Bratstvo ......................................................9-11 E. North

St. Wilkes-Barre, Pa.

Slovensky Hlasnik ........................................1601 Beaver Ave.

N. S., Pittsburgh

Rovnost Ludu ..........................................................1510

W. 18th St., Chicago

Slovensky Pokrok .....................................................309 E.

75th St., New York

Hias

..................................................................634-638

Huron Rd., Cleveland

Narodne Noviny......................................................514

Fourth Ave., Pittsburgh

Katolicky Sokol.................................................... 263

Monroe St., Passaic, N. J.

Youngstownske Slovenske Noviny............... . 239 E. Front St.,

Youngstown, Ohio

Zurnal Spojenych Majnerov ...........................1103 Merchants' Bank,

Indianapolis

Nove Slovensko.................................................. 634-638

Huron Rd., Cleveland

Nove Casy .........................................................1702 So.

Halstead St., Chicago

Semi-monthly

Obrana

...................................................................1276 E.

59th St., Cleveland

Slovensky Sokol ........................................................1424

Vyse Ave., New York

Zenska Jednota........................................................ 1276

E. 59th St., Cleveland

Prehl

ad...................................................................................

Middletown. Pa.

Monthly

Svedok..........................................................................................

Streator, Ill.

Zivena................................................................ 2007

S. Ashland Ave., Chicago

Kruh Mladeze................................................ N. S. S 524

Fourth Ave., Pittsburgh

Slovenska Mladez

...............................................................Box 1704,

Pittsburgh

Ave Maria............................................................... Box

2301, Bridgeport, Conn.

Prehl'ad...................................................................................

Mt. Pleasant, Pa.

Priatel' Dietok.............................................................

115 Hill St., Boonton, N. J.

Udalosti Sveta

................................................................................Hazleton,

Pa.

Dobry Pastier....................................................... .78

Brook St., Bridgeport, Conn.