The Last of an Era

Preserving Americana

The Evening Standard, Dec. 15, 2000

By Ted Boscia Herald-Standard Correspondent

The United States surgeon general might warn about the potentially habit-forming nature of tobacco

products, but Uniontown resident Jim Killinger isn’t worried.

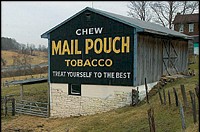

The addiction he has is not harmful, because it’s not to tobacco itself but to the folk art used

to promote one particular brand: Mail Pouch. So, when Ohioan Harley

Warrick, one of

the last men to paint ads for Mail Pouch chewing tobacco, died in late November, Killinger agreed that a part of the Mail

Pouch tradition vanished with him.

He has a lot of stories about the barns wrapped up in his painting, Killinger said.

I’m fascinated with the folk art history. After 55 years of painting more than

20,000 barns across Appalachia and the Midwest, Warrick decided to put up his industrial paintbrush in 1992 to pursue

more creative interests. However, Warrick was still compensated with a rather unusual pension: a carton of Mail

Pouch tobacco from Swisher International, Inc. every month.

Another reason that drove Warrick into retirement was governmental regulations prohibiting the

creation of outside tobacco advertisements. It came to the point where he

could no longer work around the laws, Killinger said. So, he took up painting birdfeeders and very small mail

pouch signs.

A retired state policeman, Killinger became fascinated with the work after his wife turned him onto

Warrick’s unique art form. Believed to be the last Mail Pouch

painter at the time of his death, Warrick began painting assorted Mail Pouch memorabilia, such as signs reiterating the

famous slogan, Chew Mail Pouch Tobacco. Treat Yourself to the Best.

Since that time, Killinger and his wife have amassed an extensive collection of Warrick’s

knick-knacks, which they proudly display throughout their home. Killinger even went as far as to commission Warrick to create a Mail Pouch sign this May.

Killinger fondly recalls the process he went through to receive the sign, which is now prominently displayed on the side of his barn behind his residence. I had to put in an order a year

ahead of time, Killinger said. It’s probably the last sign he ever did for a barn.

With what could be Warrick’s final creation, Killinger intends to preserve a piece of American culture. There’s a lot of history behind what he’s done, he said. He was in the process of writing a book about barns at the time of his death that tells a lot of the stories.

Killinger considers himself fortunate to have had the opportunity to meet the 76-year-old Warrick on several occasions at his Belmont, Ohio, residence. He was a real down-to-earth fellow

and a great person, he said. Harley had phenomenal recall. He mentioned to me (that) when he and his wife would drive around, he knew exactly where barns (that he had painted) were located and all the stories behind them.

While Warrick openly shrugged off his work as merely painting to make a living rather than art, the significance of Mail Pouch barns as a cultural icon is undeniable. Dotting rural outposts, his works, bastions of Americana, formed memorable landmarks for passing travelers.

Warrick’s family can take comfort in the fact that Killinger and a number of other Mail Pouch enthusiasts fight to preserve his work.

It’s a lost art, and there is no one to take his place, Killinger said.

The stuff he was doing, right up until his death, was amazing

(photos from Evening Standard)